Wait: A Saturday Evening Edition!

After work on Tuesday I went to the used bookstore downtown in our small Montana town (piles to towers of books and a dog laying on the floor who belongs to the elderly man who’s run the shop as long as I can recall).

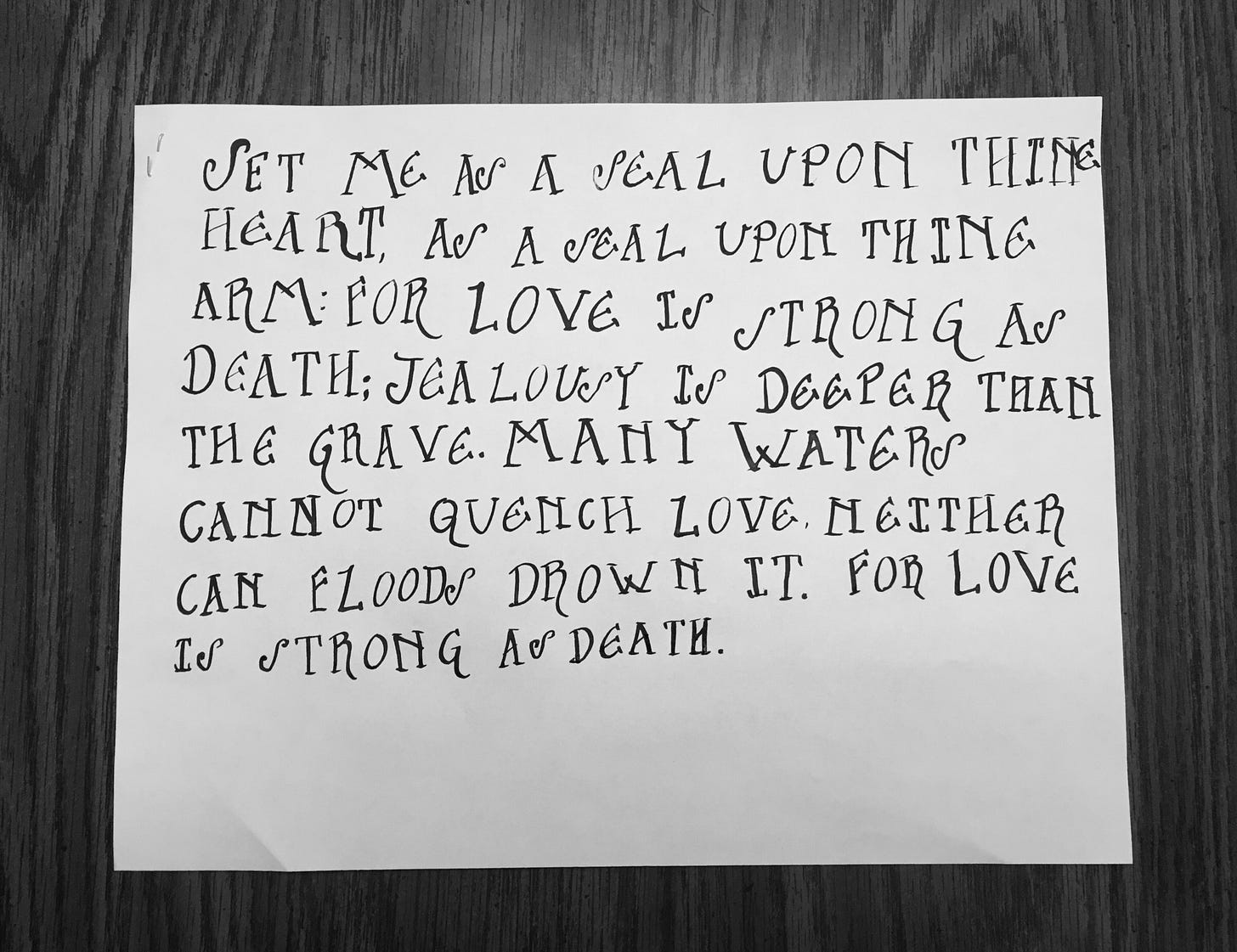

My mission: find a small 19th-century Bible to use as a prop in a short film in which a main character spends her evenings inspired by this quote:

"Very well,” said Oak, firmly, with the bearing of one who was going to give his days and nights to Ecclesiastes for ever."

—Thomas Hardy, Far From the Madding Crowd

They didn’t have any Bibles that old and kindly impressed upon me the rarity, price, and likely family history that often surround the specific kind I was looking for. The past two short films also had similar moments that forced me to face the personal-ity of history and the way books impact human lives.

But then the elderly owner asked, “Do you want to see something I won’t sell you?”

He stood up as the dog wandered over and let me give it some scritches.

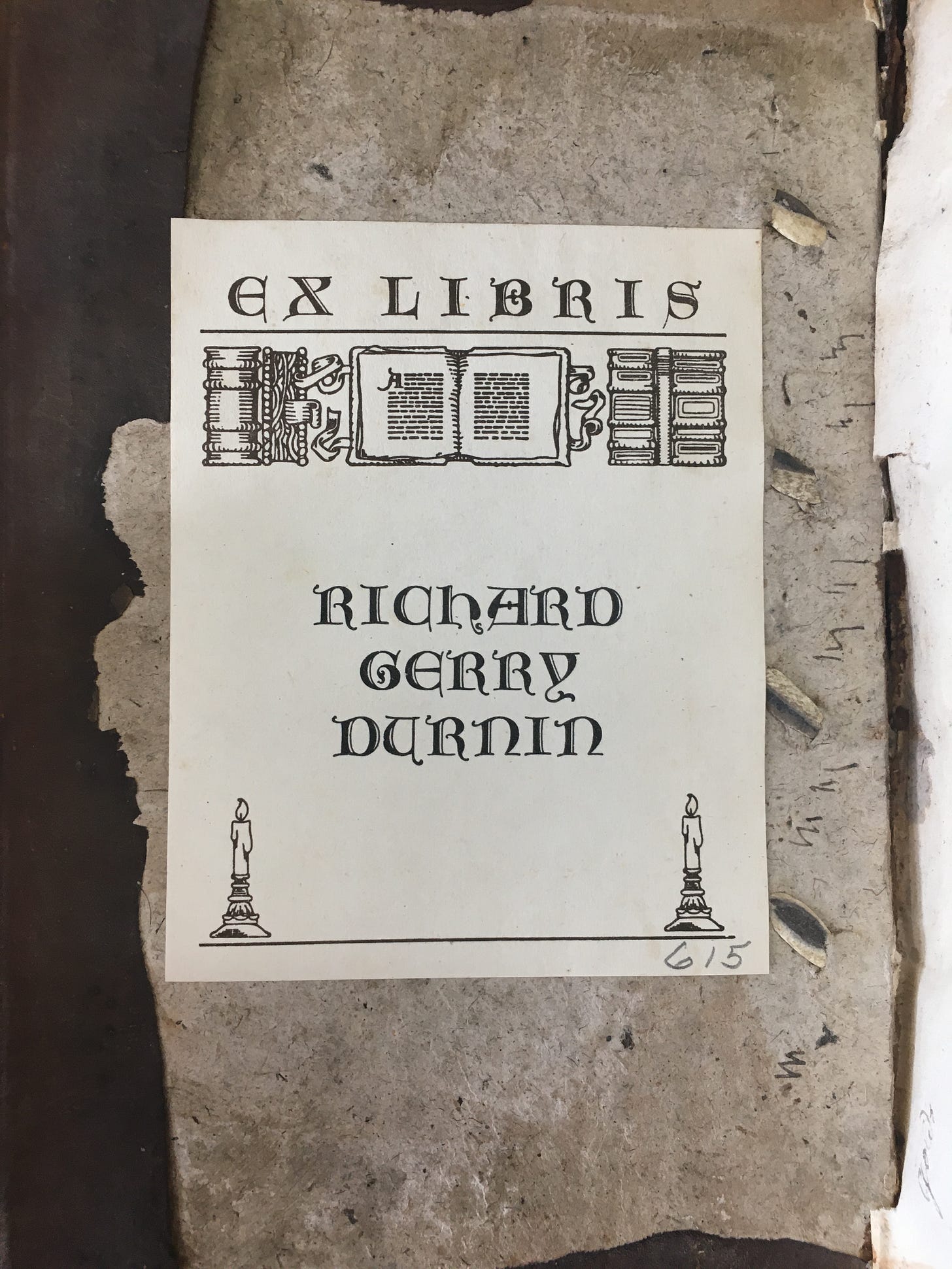

The owner placed a heavy plastic bag on the counter and with careful trembling hands took out a brown book. He set the book in front of me and motioned to look through it.

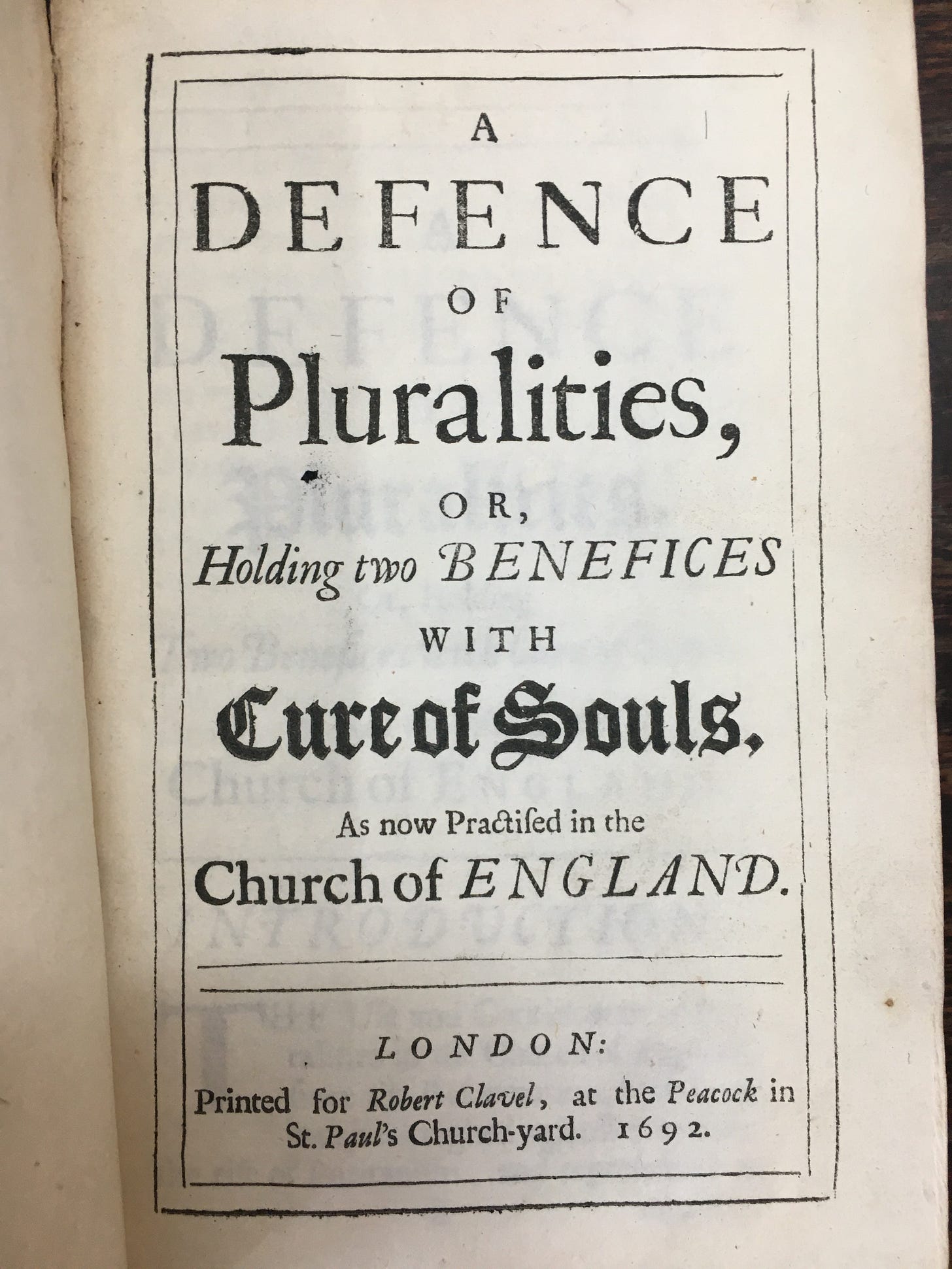

“That’s the oldest book I’ve got. 1692.”

We hushed and I delicately turned pages and gave faint and unintellectual expressions of awe and delight.

“I wish this book could talk.” The owner sat back in his chair behind the box of notecard tabs on the counter. “It may be the oldest thing I’ve ever held. It came in a box with books from the 1800s and 1700s that I put for sale, but this was made in the 1600s … Folks have told me to put a price on it, but I would just buy it for myself.

“Can you imagine the hands that have held that book? The Benjamin Franklins or George Washingtons? How did it come to America, in the 1700s? With what providence it came from back then to us here? I wish it could tell us. But it can’t. We will never know.” He shook his white-haired head. “I ain’t parting with it, for a while yet.”

Chills crept along my skin as I examined the book. Then pushed the book gently across the counter to him. I wished I could think of something apt to say, but general phrases of amazement were all I could express.

The owner carefully sealed the book from 1692 back in its plastic bag. “I don’t show it around much, but I thought you might appreciate it.”

I did and assured him of it. He bid me good luck on my quest and I gave the dog a few more scratches behind the ears and walked out of the used bookstore.

I walked along the sidewalk and tried not to cry.

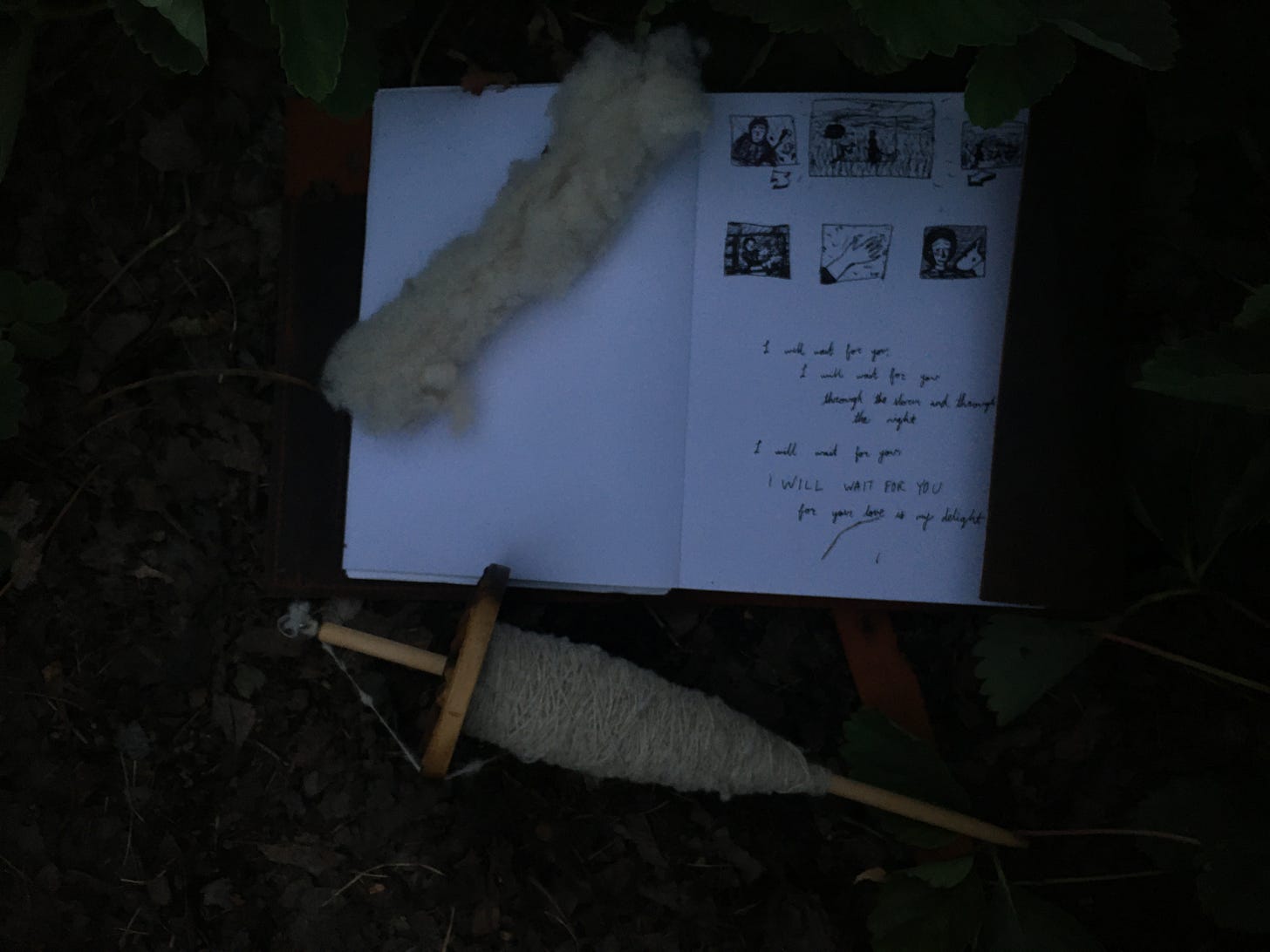

I will wait for you, I will wait for you

Through the storm and through the night

I will wait for you, surely wait for you

For your love is my delight.

Finding a Poem

That evening in November I clattered madly at the keyboard.

I wrote a scene in which a character goes up to a hill with a wood of deciduous trees—aspen?—to tend to a loved one’s grave. There are strips and scraps of colorful worn-to-bits-by-fondness fabric tied to branches about the meadow that holds the grave, that dance in woven celebration in the leaves in the wind.

Tiny hide-in-your-palm size treasures like pretty rocks, bits of carved wood, a spare shiny button, and other secret found love notes tucked among the rock border around the grave. A grave marker carved of windweathered wood; folk flowers chiseled around flowing hand-drawn letters.

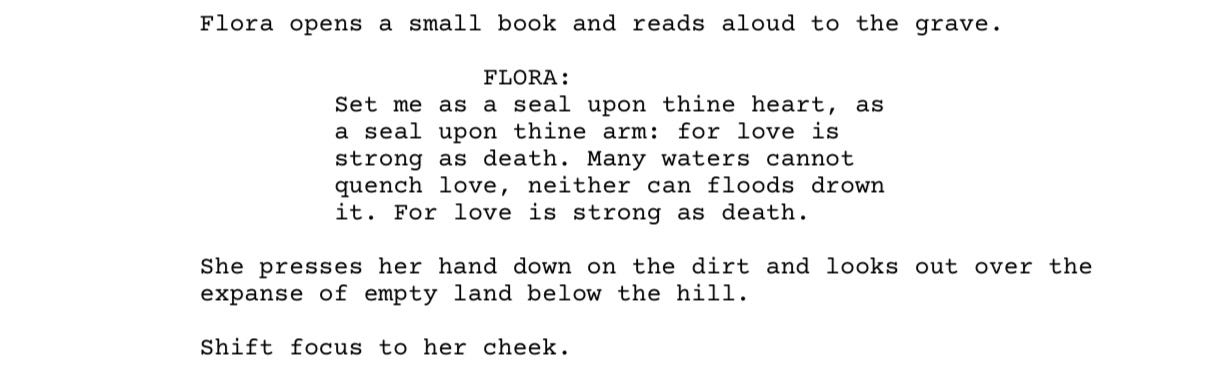

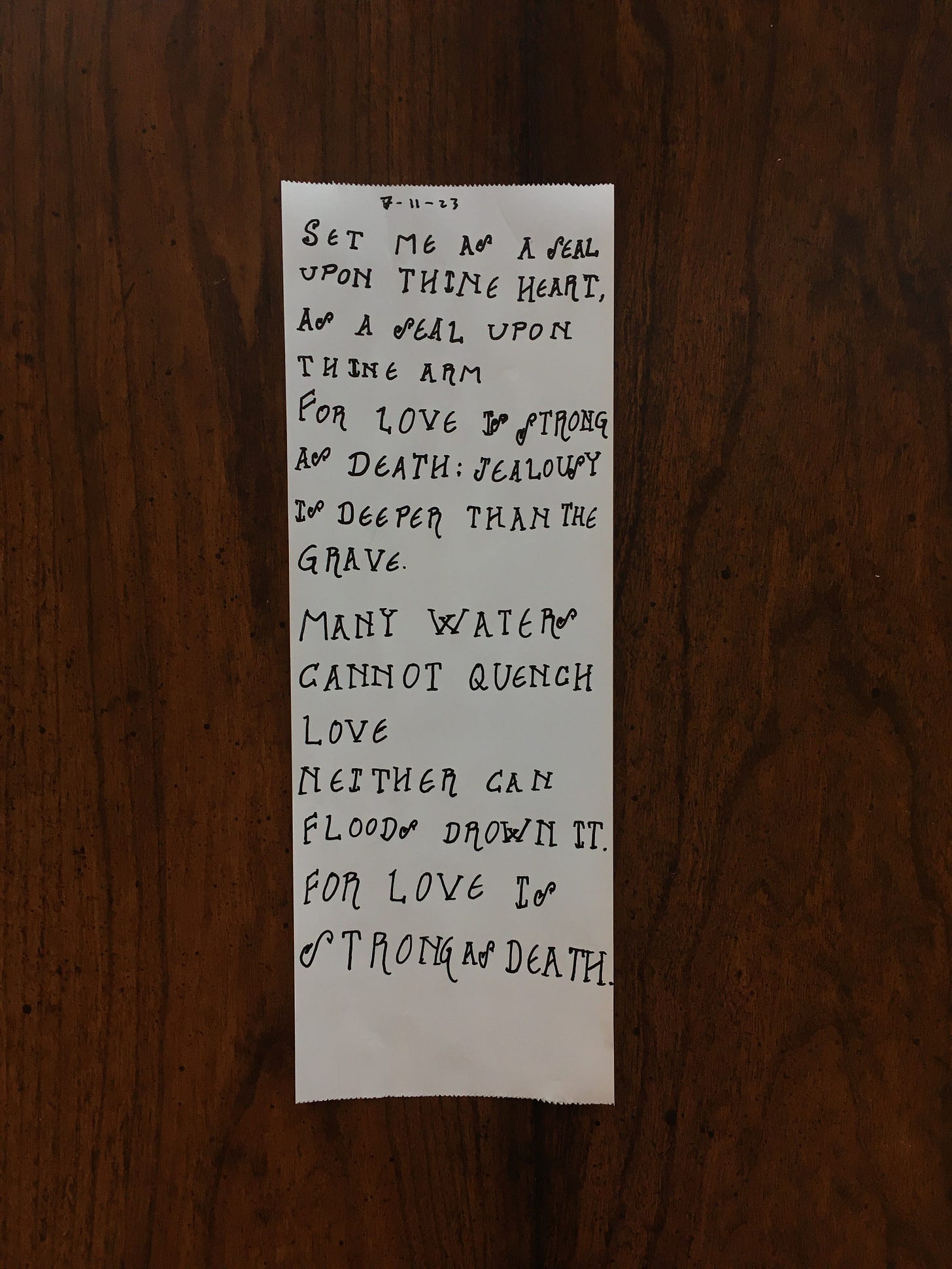

The character sits by the grave of her loved one. She brings from her cloak a small book of poetry and reads aloud a poem with her hand pressed upon the dirt… and when she has spoken the last word of the poem, she raises her chin and looks at the vast fields that stretch beyond the rolling horizon.

I was very fond of this scene immediately upon writing it.

The idea of a small book of poetry that the young woman carries every where and every chore in her pocket as a companion and means of communication.

She read aloud to the dog she found, as they waited in a log cabin at night in the sea of a prairie storm. She read aloud a poem to the grave at “plot point C2”.

What are these poems she reads, you ask?

That is a question, I reply, Let me know if you have an answer.

And thus it was November and month and month gone by. I revised the entire screenplay, tinkering with words, coyotes, rattlesnakes, teapots of cold tea…

No poem.

(I was intimidated by the search.)

On the 4th of July a friend suggested Thanatopsis. Yes!

I attempted to put it in.

The poem almost settled into the missing space, but as it touched the edges, it tinged the story with cold, with wind, with emptiness, with a sense of uneasy grasp toward meaninglessness. Neither piece was like this on its own, but when both fit together, as a whole it was ice-like: transparent enough to see a banal chaos pacing underneath.

The story rejected my attempt like a body rejecting an organ.

(I was excited: revision, fit-matching alternative options in a piece, is much more fulfilling than trying to edit blank space.)

This short film wanted something specific. Invisible to me as yet.

Now wait.

There was much in the 1928 Book of Common Prayer which needed changing; indeed, revision was first talked about in the year of publication. So it is not that all the critics of then new translations are against change (though some are), but against shabby language, against settling for the mediocre and the flabbily permissive. Where language is weak, theology becomes weakened. […]

Pelicans in the wilderness has now become vulture. Praise him, dragons and all deeps, has become sea monsters, which lacks alliteration, to put it mildly. I have been using the new Book for—approximately ten years, I think. It is now thoroughly familiar. In the old language I read, “Be ye sure that the Lord he is God; it is he that hath made us, and not we ourselves.” That is a lot more potent theology than “For the Lord himself has made us and we are his.” True. But we also need to be reminded in this do-it-yourself-age that it is indeed God who has made us and not we ourselves. We are human and humble and of the earth, and we cannot create until we acknowledge our createdness.

—Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water

Out of curiosity, I ordered a Book of Common Prayer from Thriftbooks.

I chose the copy based on its cover and it showed up brown and shabby, dated 1945 and stuffed with thees and thous. I was intimidated and didn’t feel up to the work it would require to read.

Over the months, bit by bit, the Book began to feel a little more familiar.

All translations are shaped by their time and place. They have peculiar virtues and blind spots. And the language of the original text is vital when we come to theology.

For all its biases, the King James translation now feels like falling onto a marshmallow, or being wrapped in an eiderdown comforter. The language is soft for the tongue and engages the visual imaginative, and it’s often plain weirder than modern translations I’m familiar with.

This summer I’ve been reading the Time Quintet. (I was stoked to see the pelican in the wilderness in Many Waters.) I have never read anything like how she weaves science fiction with a deeper-than-language-cosmic-melody that Mrs. Whatsit attempts to translate with—you’ll never guess—in chapter 4 of A Wrinkle in Time.

It is a recipe written in life the past few months + the story itself:

You may recall that carrier basket essay a few weeks ago.

Add a wedding ceremony, a sprinkling of happy tears.

A pinch of knowledge that the short film doesn’t want a poem about panic and emptiness.

Madeleine L’Engle’s love for the language of scripture (as melody of cosmos).

Pour in a teaspoon of Requiem in a World-Wood.

“Part of grief is laying to rest, reverse extraction. Return. Grave tending is a form of earth tending, but also a form of story tending, in which the dead are allowed to rest in our memory as well as the soil. Our memory is literally earth-bound. Grief requires physical spaces and it may be that the very words and landscapes we need to recover are the ones that our dead want to offer us. But they rely on the agency of the living. ‘Dona eis requiem,’ the priest says at the Requiem mass: ‘Grant them eternal rest.’ Perhaps if we can learn to say these words to our dead, words we do not seem be able to say to oil, to coal, to gas – we can begin to grieve. A burial is, after all, a reverse extraction.”

—Anna Hatke #

Well.

It looks like a gift. Again, a gift.

The past week has been towers built and slammed in the side by frisbees; wooden blocks tumble and clatter to chaos.

Forced to face incompetence in self. Plans constructed for safety, an anxious self-centered, near burnt-out pressure. Taken away to reveal empty hands.

Waiting.

Waiting for patience.

Waiting, empty hands starting to learn how to receive, floating in deep love.

The Storyteller: Fearnot

Quote: 🏹📜🌻

“I have never served a work as it ought to be served; my little trickle adds hardly a drop of water to the lake, and yet it doesn’t matter; there is no trickle too small. Over the years I have come to recognize that the work often knows more than I do. And with each book I start, I have hopes that I may be helped to serve it a little more fully. The great artists, the rivers and tributaries, collaborate with the work, but for most of us, it is our greatest privilege to be its servant.

When the artist is truly a servant of the work, the work is better than the artist; Shakespeare knew how to listen to his work, and so he often wrote better than he could write; Bach composed more deeply, more truly, than he knew; Rembrandt’s brush put more of the human spirit on canvas than Rembrandt could comprehend.

When the work takes over, then the artist is enabled to get out of the way, not to interfere. When the work takes over, then the artist listens.

But before he can listen, paradoxically, he must work. Getting out of the way and listening is not something that comes easily, either in art or in prayer…

Someone wrote, “The principle part of faith is patience,” and this applies too, to art of all disciplines.”

—Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water