A Year of Howards End ☕🌸🌧

Hey pals! *Bumps your shoulder awkwardly with a fist*

It’s another week of Loch Ness Robots being slightly late, but that’s okay because it’s something I do just for fun!

Leonard Bernstein tells me more than the dictionary when he says that for him music is cosmos in chaos. That has the ring of truth in my ears and sparks my creative imagination. And it is true not only of music; all art is cosmos, comsos found within chaos.

—Madeleine L’Engle, Walking on Water

Last week I walked around town under blue skies and sunshine and thought that maybe art is a form of naming; a harmony in a song or a passage in a movie or a paragraph in a book might encapsulate an experience you’ve had and by the simple act of representation do what I think perhaps the biblical act of Naming does: it makes something more real and more of itself, and it also places it in the world and gives perspective. The movie Bridge to Terebithia did this to me with grief when I was 14. All the Books gave a lot of us proof that a feeling we may have thought was isolated to us—you or me as an individual—was felt by a large group of people.

You read something which you thought only happened to you, and you discover that it happened 100 years ago to Dostoyevsky. This is a very great liberation for the suffering, struggling person, who always thinks he is alone. This is why art is important. Art would not be important if life were not important, and life is important.

—James Baldwin, Conversations with James Baldwin

Late modernity sometimes contrasts the biblical view of reality with what is calls a pathos of finitude: people are meaningful and precious precisely because they will not last forever, because they die and are no more. There is beauty and dignity in the flower we know will soon wilt, in the sandcastle that will be washed away by the next tide, and in the human whose life will ebb away. This is sometimes contrasted to a Christian view of eternal life, which, it is argued, cannot invest existence and humanity with the same delicate, ephemeral dignity. Regardless of whether the dignity and beauty flowing from the pathos of finititude are well founded, this dismissal of Christianity fails to recognize that the biblical view of the world has its own pathos: the pathos of contingency. Nothing in this world is necessary because the universe itself is unnecessary. It is far from clear that a naturalistic view of the world can claim any such thing with confidence, and this tends to the conclusion that the beauty, delicacy, and ephemerality of existence are on the side of the biblical account, with an inhuman, anarchic chance on the side of monism.

… Hart is skeptical that even today, two thousand years and more after philosophy’s explosive rise, it has yet come to terms with this biblical claim. Indeed, philosophy shies away from gratuity because it is so disarming; it robs us of certainty and control and it shows that we cannot possess the fundamental reason for the universe’s existence as the necessary product of a chain of reasoning.

—Christopher Watkin, Biblical Critical Theory pg. 61

I am officially working toward filming another short film with a small and mighty group of friends in April. It’s that sibling fairy tale in a forest. If I haven’t told you in person, I’m sorry! Also, I have not learned how to tell people about what I’m making yet. There are a lot of people who are friends and family who don’t know about Loch Ness Robots because I was mortified to share it when it first began and now it feels awkward to tell people that I’ve been doing this newsletter for over a year and haven’t told them about it. My bad. Yikes. Well, at least we know.

It’s been about a year since I watched the 2017 miniseries adaptation of Howard’s End and was shocked when it was relevant to a lot of aspects of my life at the time. I identified with many of the characters. I had the same questions. I saw my own economically privileged idealism, savior complex, devotion to art and literature, and blindness in the Schlegel sisters.

“So often I feel we live, chattering away, at the edge of a great abyss. I don’t want to close my eyes to it, or comfortably pretend it isn’t there, but I don’t want to live in it. Is that very wicked and selfish of me?”

—Howards End (2017 miniseries)

Ruth Wilcox was an archetype I’ve wrestled with for a few years that the story humanized. When Leonard Bast goes on a walk at night and asks what’s the point of living your life in a room at work and tries to read Ruskin, I wholeheartedly empathized as I was adjusting to a new job (sleep-deprived), trying to understand Morris and grasping for thoughts that weren’t mine to catch. And I get the potentially destructive Wilcox appeal.

Over the next few weeks, I read the book. I’d walk home from work and lay on the couch and read a chapter until I started to doze off—pleasant but annoying—and go on till my brain had whirred to life again in wonder. It was like drinking a glass of sweet, cold water.

I didn’t always agree with the author’s choices or his “take” on the events in his book. But when E. M. Forster described Leonard imagining the letter he’d write to his brother and later in chapter 14 talk about his walk—that was a lecture on honesty that changed my approach to how I wrote for the rest of the year.

excerpt from Howards End, Chapter 6

Then [Leonard] went back to the sitting-room, settled himself anew, and began to read a volume of Ruskin.

“Seven miles to the north of Venice—”

How perfectly the famous chapter opens! How supreme its command of admonition and poetry! The rich man is speaking to us from his gondola.

“Seven miles to the north of Venice the banks of sand which nearer the city rise little above low-water mark attain by degrees morass, raised here and there into shapeless mounds, and intercepted by narrow creeks of sea.”

Leonard was trying to form his style on Ruskin: he understood him to be the greatest master of English Prose. He read forward steadily, occasionally making a few notes.

“Let us consider a little each of these characters in succession, and first (for of the shafts enough has been said already), what is very peculiar to this church—its luminousness.”

Was there anything to be learnt from this fine sentence? Could he adapt it to the needs of daily life? Could he introduce it, with modifications, when he next wrote a letter to his brother, the lay reader? For example—

“Let us consider a little each of these characters in succession, and first (for of the absence of ventiliation enough has been said already), what is very peculiar to this flat—its obscurity.”

Something told him that the modifications would not do; and that something, had he known it, was the spirit of English Prose. “My flat is dark as well as stuffy.” Those were the words for him.

—E. M. Forster, Howards End (Chapter 6)

There was a paragraph on mountains in Wales that doesn’t make sense when you pull it out of its position in pages of travel description, but it verbalized a feeling about some hills I grew up with that’s lived in my bones since I was very young.

I don’t know a lot about Howard’s End in a literary analysis sense. I don’t know if you should read it. But so many moments in it shimmer in my imagination and refreshed me as I read them and made my life bigger afterwards. I like it and I don’t fully agree with its philosophy.

“How Helen would revel in such a notion! Charles dead, all people dead, nothing alive but houses and gardens. The obvious dead, the intangible alive, and—no connection at all between them! Margaret smiled. Would that her own fancies were as clear cut! Would that she could deal as high-handedly with the world! Smiling and sighing, she laid her hand upon the door. It opened. The house was not locked up at all …

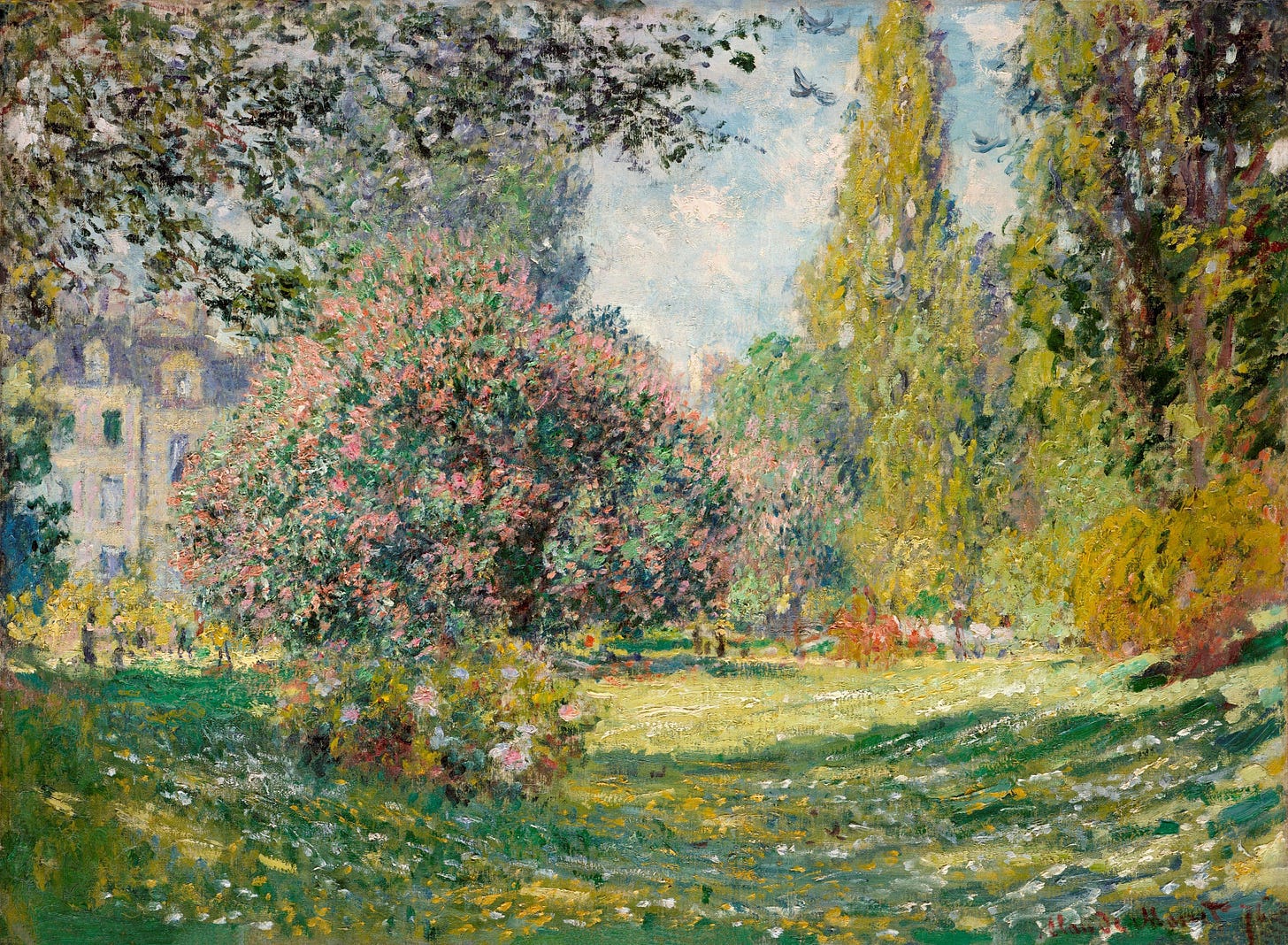

The garden at the back was full of flowering cherries and plums. Farther on were hints of the meadow and a black cliff of pines. Yes, the meadow was beautiful.

Penned in by desolate weather, she recaptured the sense of space which the motor had tried to rob from her. She remembered that ten square miles are not ten times as wonderful as one square mile, that a thousand square miles are not practically heaven. The phantom of bigness … was laid forever when she paced from the hall at Howards End to its kitchen and heard the rains run this way and that where the watershed of the roof divided them.”

—E. M. Forster, Howards End

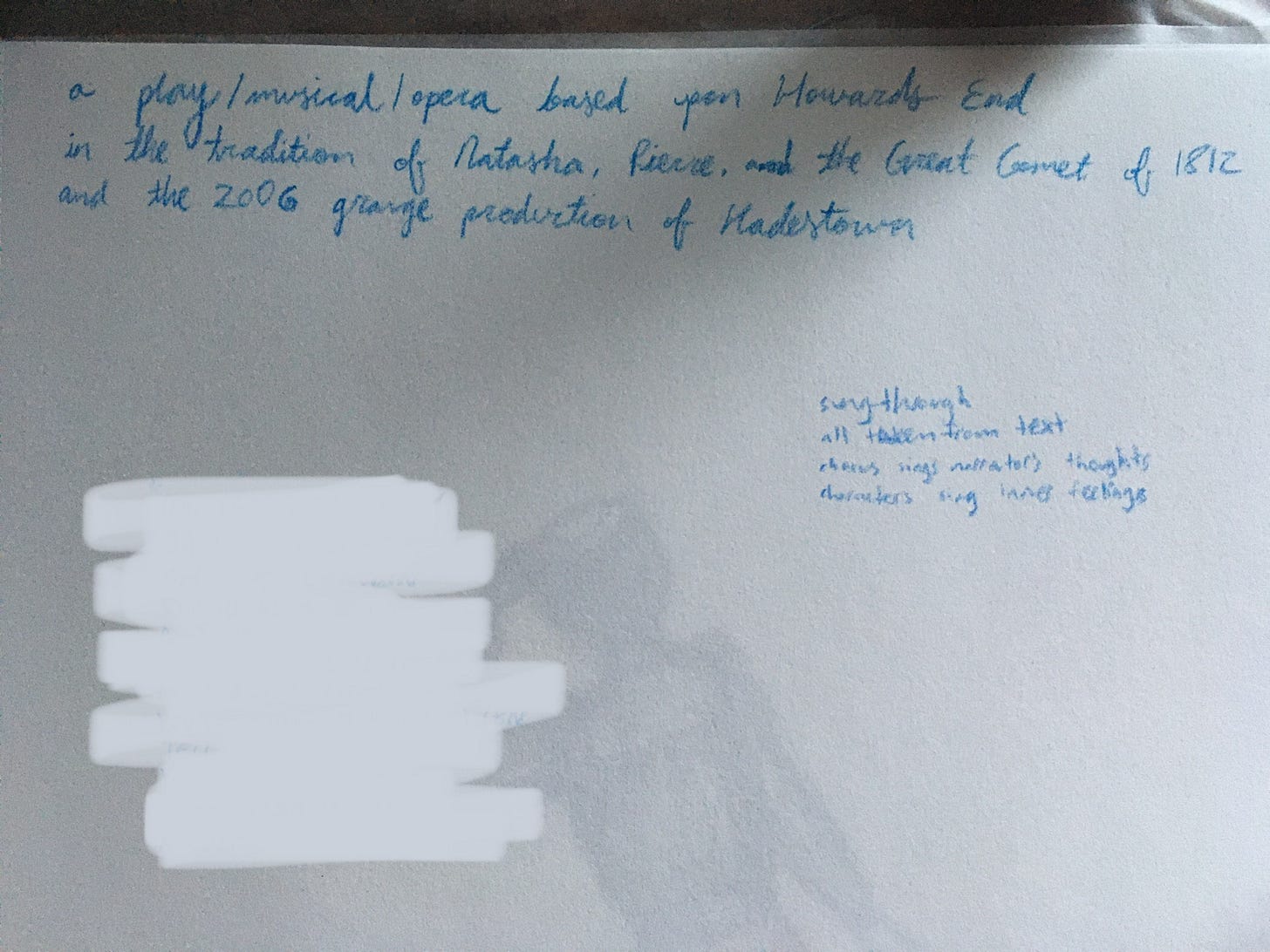

There’s an empty building on Main Street in my town. It’s got big “for lease” signs in the windows and has for the past year or two. I enjoy looking into the windows and imagining how I would transform the spacious historical space into a theatrical event for a few evenings. I was obsessed with the idea for a while last spring and summer and felt a lot of pressure to generate enough worthy material to make a show to produce in that building before someone leases it and puts a store inside. When I walked home from work, I wrote a lot of snippets of songs for a musical inspired by Howard’s End. They don’t reflect the way the book reads you, but they are a reflection of me looking at the characters and places inside it and putting them in a container to share.

I love how my brain’s response to being tired is always, “Why have you not composed and directed a full length opera yet WHY HAVE YOU NOT COMPOSED AN OPERA YET” every time. But like legit why have I not composed a full opera by the age of 20, what a slacker.

—Mailli, June 2023

Last night I relistened to all of these for the first time and thought it might be fun to record a little lowkey acoustic collection of songs inspired by Howard’s End from 2023. I don’t feel that pressure anymore. (As I realized last February, my brain has a chemical imbalance and likes to imagine the hardest way to make itself feel good.) I like the silly little songs and I am happy to remember them.

The newsletter is a day late because I didn’t record all the music in time yesterday. You may or may not get an email with Howards End music at some point in the future.

I don’t know?!

From “A Backyard Song,” Loch Ness Robots

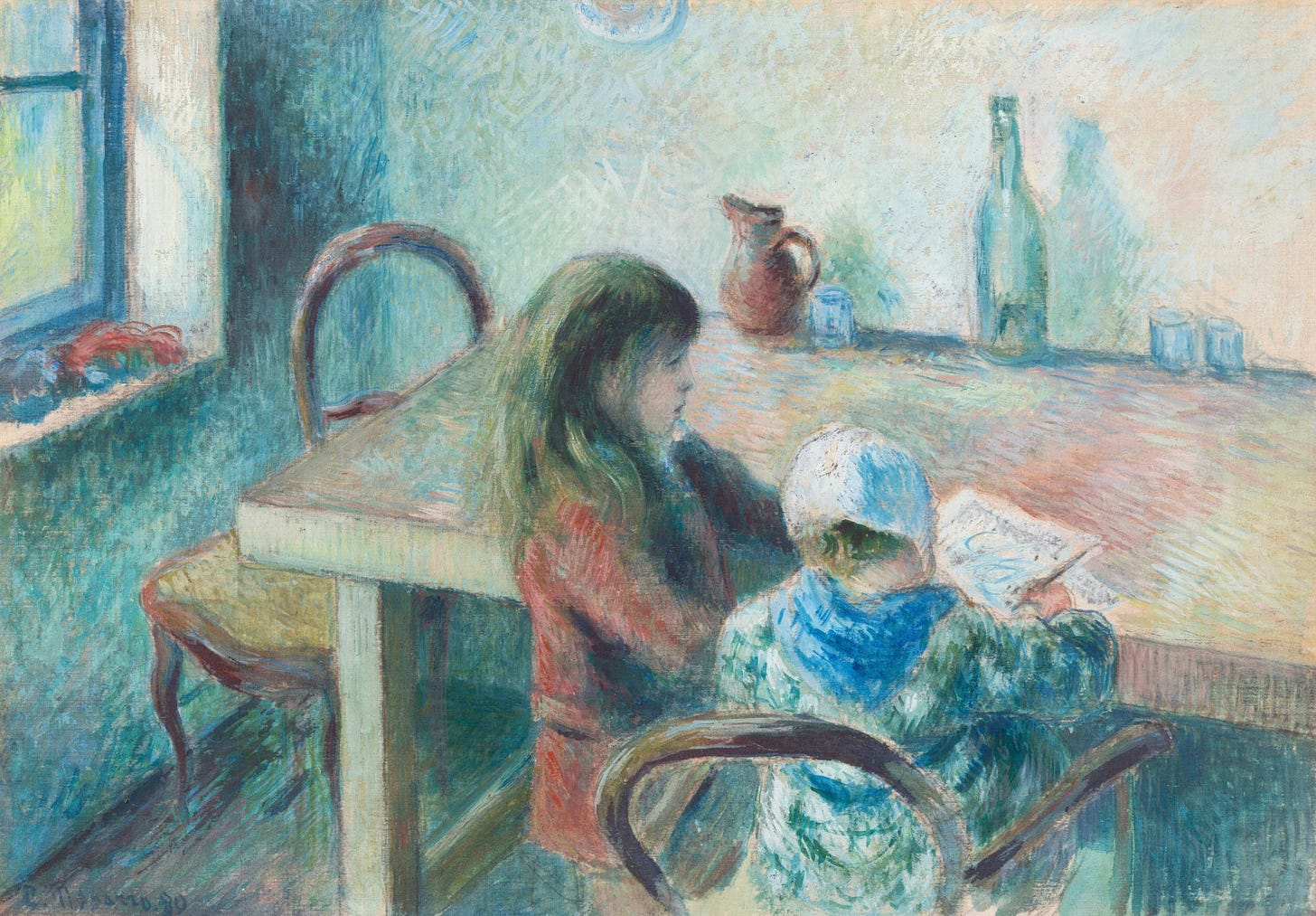

I was tired last week. One evening when it was all I could handle I took my phone, headphones, the paperback copy of Howards End with a painted cover of a rainy-day sitting room, and a loop of two chords on piano, and I went out to the backyard to sing at dusk.

I wanted the novel for words. I only had the capacity to play with music at the moment. The two chords lent themselves to a black and gold passage that takes place on a hill on (I think) a drizzly day.

*Disclaimer:* some (a lot) of y’all who read Loch Ness Robots are musicians who know a lot more than I might ever learn, and I deeply respect your tastes, experiences, and you as artists.

This is a make-up-a-melody-in-the-minute-then-layer-instinctive-harmonies-as-an-experiment-to-see-which-notes-work-together-and-learn-about-cluster-chords-with-my-brain-turned-off-because-I’m-literally-so-drained-at-8:30-pm.

A Quote:

“Decisions were a delight after the curse. I loved having the power to say yes or no, and refusing anything was a special pleasure.”

—Gail Carson Levine, Ella Enchanted